I have always been curious about how people end up doing whatever it is they do for a living. When they were in college, was this what they had envisioned they would be doing with their lives? High school? Further back? Do they have a job that is completely unrelated to why they went to college? Do they have a degree that they don’t even use? What about those people who opted not to attend college? Was that always the plan? College isn’t for everyone and plenty of skilled jobs don’t necessarily require a college degree. Carpenter, cabinetmaker, plumber, house painter, roofer, electrician, machinist! None of these specifically require a degree. Perhaps some trade school education, although many tradesmen get on-the-job training and never see the inside of a classroom.

This leads me to do something in this blog that I have never done before. I am going to write about how I ended up becoming a machinist these past 43 years. As always, I’ll try to keep it entertaining and maybe you will learn something new along the way. You see, I’m a journeyman machinist, licensed by the state of California. This wasn’t the plan and, had you asked me in high school, this was the last job in which I would have expected to find myself. And yet, here I am for forty-three years.

The plan, since Junior High School, was to be an architect. All through Junior and then Senior High School I took drafting classes. Hours and hours of architectural drafting. I didn’t do much else because I really didn’t know what else to do. My opinion of high school is that they are very good at teaching names, dates, and numbers. But they don’t do a very good job preparing young people for what comes after. Whether it be college, or trade school, or whatever it is they wish to do with their lives. I think high school should be a place that gives you some guidance and direction on how to achieve your goals as an adult. There should be a class where every student identifies their career goals and then they are given assignments to further those goals. Maybe writing to colleges or interviewing someone locally doing that job. Maybe discussing what they will need in terms of education. This is what you want…this is how you get it. I wanted to be an architect, but what kind of architect? Design subdivisions? Tract housing? Design unique houses utilizing available light, space, and surroundings (very Frank Lloyd Wright)? Commercial/industrial buildings? High rises? There are a lot of choices. How do I narrow these down and focus on a specific goal?

Actually, by the time I graduated, all I really wanted to do was take a year off before I started working on my architecture degree. But I didn’t know what I wanted to do with that time off. It would be nice to say I wanted to do something romantic, like travel, but I didn’t have the money for that. I also remember my dad being very disappointed that I didn’t want to start college immediately. He said “if you take a year off, you’ll never go back.” He was almost right. While my grades were good, mostly A’s and B’s, they weren’t good enough to pull in a scholarship. The irony of that is the fact that Dad, while expressing moral and parental concern over my decision to stay out of college, was flat broke. Had I opted to attend college immediately after high school, I don’t know how he expected to pay for it. And I certainly didn’t have a clue. It’s funny. At age eighteen I was very unfocused. Aren’t most eighteen-year-olds? I kinda, sorta knew what I wanted to do with my life, but I lacked a plan. In those days the “plan” was to party. To coin that famous cliche, if I knew then what I know now… I probably would have taken that year off, saved as much money as I could, and laid out a plan. Since we didn’t have the Internet then, I would have arranged to meet local architects and get their insights. What would they suggest I do, as a young man seeking a career in that field? Unfortunately, I was not nearly so direct and self-confident in those days.

I had no skills to speak of, at least none of which I was aware. In high school, I had worked part time in a little mom & pop burger stand called Mr. Big Burgers. After graduation I decided to continue working there until I figured this out. Meanwhile, a good friend kept urging me to get a real job. Like he had. At Carl’s Jr. I figured that was, at least, a step up. Not sure if it was furthering me along my path to become an architect. Funny thing about that, my friend and I were both over 18 and could legally work past 10:00 o’clock at night. Back then 18 years-old-and-older available to work evenings were something of a Unicorn. I probably had the job before I finished the interview. My friend, who was looking forward to working with me, had been doing some things that got him in trouble with management. Ultimately it got him fired. So, I stepped in and took his place. No hard feelings.

Carl’s Jr. ended up being about a two-year detour. And it appeared that Dad had correctly predicted that I wouldn’t return to school. The fact that I get along well with people, I work hard at whatever it is I am assigned to do, and I tend to learn quickly, all worked to propel me up the so-called corporate ladder. I eventually became a store manager at the age of 20. To this day I think they promoted me before I was ready. The fact that I lasted less than six months as a manager is probably proof of that. Carl’s Jr. is the only job I’ve ever been fired from.

Finding another job was challenging. I didn’t want anything to do with the restaurant business. I couldn’t afford college. I didn’t have any skills or abilities. I didn’t have any superpowers. Besides, crime fighting is overrated. It’s cool, but the pay sucks. Pages fell off the calendar and suddenly it was three months later. Somewhere in there I turned 21. My dad had a job where he worked with a lot of local machine shops. He kept telling me he could get me a job as a machinist. The last thing I wanted was my dad to find me a job. But with that fourth calendar page hanging by a thread, the rent due, and the checking account drained, I had no choice but to cave in. Heck, I didn’t know the first thing about being a machinist. I didn’t know the difference between a mill or a lathe, much less how to operate either one of them, but my dad set me up with an interview and I dutifully showed up on time. I had actually met the owner, Jim Klune, a couple of times as a friend of my dad. We kind of knew each other. Jim told me if I wanted to be a machinist, his shop was not the place to learn. They did a lot of sheet metal work, which is very specific. He said, if I wanted to learn to be good all-around machinist, I should meet a guy that owned a small machine shop in Burbank. His name was Burr Dean, and he did a little bit of everything. Jim made the call, and arranged for me to meet the man. He then told me, if that didn’t work out, I could come back and he’d put me to work doing something. Maybe just sweeping floors until he could find a position for me. So at least I had a job… somewhere!

Back then, I didn’t know if I wanted to be a machinist. I just wanted a job so I could pay the rent. It turns out I did have some skills. Where have you been hiding all my life? The job came to me naturally and Burr liked my work. Like Jim Klune had said, Dean Engineering was a small shop. Just Burr and three of us. One of the guys, also named Jim, went to high school with me and graduated a year behind. The other guy I never got to know very well because he quit the first month or two that I was there. Needing a machinist, I pointed my brother, who needed a job, in Burrs’ direction and soon we were both working there. Dad, always wanting the best for his boys, turned Burr onto a journeyman apprenticeship program offered by the state of California. In order to get a journeyman license in four years, we had to work full time in a machine shop and run different machines during that period. Mills, lathes, saws, drill presses, and grinders were the norm. Maybe a little CNC for good measure if the shop was so equipped. Back then CNC was a pretty new thing and not everyone had access to it. Thankfully, Burr was always into the newest and latest toys and Dean Engineering was more of a CNC shop than a manual shop. We also had to go to school to learn various disciplines. One class per semester, which worked out to eight classes during the four-year program. Classes included trigonometry, CNC programming, blueprint reading, and general machine shop, among others. At the end of the four-year program, we would have 8000 hours of practical experience in machine shop plus all of the tools, pun intended, necessary to perform our job as machinists. unfortunately, the state no longer offers this program. I’m not sure if other states do or not. Instead of a journeyman license, you can go to Community College and get an AS degree.

We started off attending classes at a local occupational center. My take on this, was that these were retired machinists hired to teach the class. They knew about machining but, whether or not they knew anything about teaching, was questionable. During the second semester all I remember is this guy would spend the first half hour talking about the raw deal he got as a machinist. I looked into transferring everything over to a Community College, reasoning that these guys might be actual teachers with a degree and everything. Fortunately, I was able to do just that and, as it turned out, I did go back to college. Not only did I go back to college, but I realized how much I missed the whole educational experience. What is it they say about not appreciating something until you no longer have it? The brain is like any other muscle, and I had let mine atrophy these past few years. Each semester I took my obligatory machinist class, but I would also take two and sometimes three other classes, in addition to working full time. I took classes that I enjoyed which made it a lot easier. I remember taking astronomy, history, oceanography, and creative writing (what is surprise there) among others.

As happens a lot in industry, Dean Engineering went into a little bit of a business slump. Burr held onto us as long as he could, but he eventually had to let both my brother and me go. Jim had been there the longest so it was only fair that, if Burr was going to keep someone, that it would be Jim. I’m happy to say that they got through that little rough patch and others as well. Dean Engineering is still in business today and my high school chum, Jim, is still working there. I went on to take a job for a company called Rigger Engineering. They were probably the only oilfield related machine shop existing in the San Fernando Valley at that time. I finished the program and got my journeyman license while working for Rigger Engineering and worked there for 28 years. The first 14 years I was a machinist in the machine shop. The second 14 years I was a 49% owner in the business.

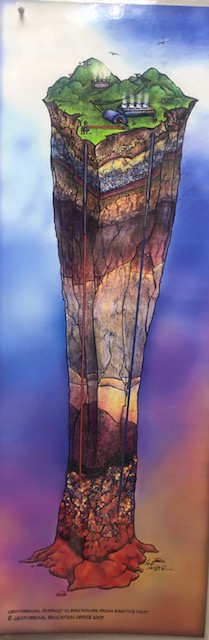

The company was a bit of a one trick pony. Most of the manufacturing we did was a tool used in the oil, gas, and geothermal industries known as a liner hanger. Specifically, it is a Burns liner hanger, developed in 1939 by the Burns Tool Company, with R&D money supplied by UNOCAL or, better known at that time, Union Oil of California. I could probably write a book about the history of that tool and my 28-year association with it. What I will say here is that, by the time I bought into the company, the use of that tool was in general decline. There were a lot of other manufacturers that produced similar tools that included a lot of bells and whistles that we could not supply due to design limitations. When I bought into the company, I specifically targeted the geothermal industry. They are a smaller offshoot of the oil and gas industry and use the same tools and techniques for drilling their hi temperature steam wells. They also do a fraction of a percentage point of the sales volume you’ll see in oil and gas. Their main objective is to keep costs down as much as possible. They didn’t need a liner hanger that had a lot of bells and whistles and did a lot of tricks. They needed a tool that was functional, reliable, and inexpensive. There had been a big geothermal energy push back in the 80s and the government was offering grants and subsidies in order to incentivize these geothermal drilling companies. Then the price of oil crashed, making it a cheaper energy source and a stronger competitor to geothermal. As the incentives disappeared, so did the geothermal companies. I got lucky with the timing. Geothermal energy was once again coming into vogue and this time it wasn’t being supported artificially by government incentives. It was being driven by environmental concerns to use cheap, clean, alternative energy. Geothermal, this time, got traction and appears here to stay.

Timing is everything and I will admit I got lucky. When I became a partner in 1996 geothermal was just becoming hot again. Pun intended. We developed a connection in Mexico and started selling product in the Cerro Prieto Geothermal field just across the border from Mexicali. We were trying to use that as a springboard to develop a reputation and a name in the international market and that took time. For the first seven years of my ownership, we averaged about $150,000 in sales and were just hanging on by the skin of our teeth, whatever that means. Back in 1996, none of our sales were in geothermal and none were international. Once we get our footing, sales began to take off. I left the business in 2010 and sold my interest to my partner in 2011. In 2010, the year I left, we did a little over $950,000 in sales. We just missed our first ever $1,000,000 year. They sailed right past $1,000,000 in sales the following year. Probably 80% of those sales were in geothermal with almost all of it going overseas. In fact, one of our largest customers was in Turkey.

That’s my story. Hope you found it interesting and perhaps learned something. I sort of fell into this profession and, like I said, it’s the last thing I expected to be doing. I suspect that may be true of a lot of people. Sometimes I wonder where I would be today had I been a bit more motivated to get my degree in architecture. I certainly would not be the same person. Who I am has been shaped by sixty-three years of experiences. Change those experiences and you change the man. Just as a follow up, I came to work for my current employer, Valley Perforating in Bakersfield, about six months after leaving Rigger Engineering. These days I leave the ownership headaches to someone else and I’m happy just to be a machinist. That’s really my best me. I’ve said this before, but it bears repeating. I have come to view myself as something of a Unicorn. One of the hardest things about being a machinist is the math. YOU NEED TO HAVE A FULL UNDERSTANDING OF GEOMETY AND TRIGONOMETRY. It seems guys coming into manufacturing today are too lazy to get the necessary training. The one commonality I see all the time is these guys don’t know how to do trigonometry. I see a lot of guys that come to work in the machine shop, but they are not machinists. At best they are machine operators, at worst, button pushers. Talking to our HR department, I hear that they are seeing fewer and fewer people come in with the necessary training and/or skills to be considered true machinists. Where once CNC was considered an expensive toy, the manufacturing industry has now embraced the concept. There are parts being made now that cannot be made any other way except via CNC. It is my understanding that in large machine shops they compartmentalize everything. In the CNC department there is one guy that is strictly an operator. He feeds the part in and pushes a button. Something happens and a tool breaks, he steps aside and another guy that does nothing but tooling steps in and replaces the tool, making sure everything is realigned. If they are starting a new job and they need to have a special set up there is a guy that does nothing but setups. And then of course you have a guy that does nothing but write programs. The downside of all of this compartmentalization is guys that know how to run manual mills and manual lathes are becoming scarce, bordering on obsolete. Same thing can be said of CNC guys that can do a set-up, dry run and edit the program, run the part, and replace broken tooling…all done by the same guy. Guys that can run both manual and CNC machines, including programming? At my company there is only one guy that can do that. That would be yours truly. I am a Unicorn in another sense as well. That Burns Liner Hanger? As far as I know there are only three companies that make it. Rigger Engineering, some company in India I have never dealt with, although I’ve checked out their website, and Valley Perforating, my present employer. Valley Perforating was making the hanger (before I came along) as a reverse engineered version of the Rigger Engineering hangar. When I entered the picture, I saw a couple of design improvements they had made which I liked. I also saw a couple of mistakes they were making that would have gotten them into trouble sooner or later. The bottom line is this is not an easy tool to manufacture. When I left Rigger Engineering, it was my understanding that they had a lot of manufacturing issues they had to work through for the first six months to a year. Even if you were handed a complete set of blueprints and you made a tool from those, there are a lot of little tricks in the assembly process that you would only know from experience. That being said, the fact that there are only three companies known to me that manufacturer this liner hanger, and there are probably only a few people in each company that really could build one from start to finish, I would say you can count the number of people on the entire planet that can build one of these tools on two hands. I guess that makes me an albino Unicorn.

If I could, would I change any of it? Probably not. It’s been a fun ride and I have met some of my best friends because of my decision to cave in and let my dad help me get a job. I have been places and seen things I would not have been able to as an architect or Manager of a fast-food joint. I’d do it all over again. I hope you will indulge me for one more week. I had a very interesting assignment at work last week. It shows how complex my job can be and I was going to blog about it. LOTS OF PICTURES! I started writing about how I came to be a machinist, and this was the result. I never even mentioned this project until I was over 3000 words in, and I try to keep my word count to between 2000 and 4000. So next week I will discuss the complexity of doing what I do. I’m kind of like Scotty in Star Trek that way. It really is fun. So, until then, swing for the fences!

AND REMEMBER TO BOOKMARK THIS SITE SO YOU CAN COME BACK TO IT!!!