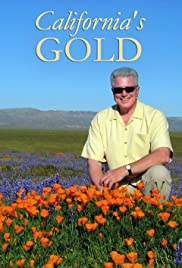

Welcome again faithful readers. Can you believe Christmas is in just 10 days? WOW! With this week’s blog I will be launching a new feature. From 1991 until 2012 there was a television show on PBS, at least in California, appropriately named, California’s Gold. The show was hosted by, and was the vision of, a gentleman by the name of Huell Howser. Huell was a big old Okie, born and raised in Tennessee, but had adopted California as his home. The show, shot with a single camera, found Huell traveling around the Golden State to various sites of interest, of which most people knew little, if anything, at all. He would introduce his subject and then profile it in the form of a 30-minute documentary style program. One week he might be reporting on In-N-Out Burgers and the next he would do a story on Yosemite or the Salton Sea or perhaps the small town of Lee Vining. Much of the program would consist of interviews with local residents viewing the subject matter from their perspective and position of expertise. Huell had a down home, folksy interview style peppered with a lot of wow’s and that’s amazing’s. He did not talk down to his subjects and you could see he was genuinely interested. He had a way of getting the interviewee to open up and was able to make even the most mundane subjects shine with a new light.

Sadly, Huell passed away in 2013 at the age of 67. As a tribute to him I am dedicating this new feature of my blog to his memory. I will periodically try to shine a light on some place I have visited and found interesting. It will mostly be California, especially in the beginning, but I am not limiting myself to just California. For instance, I hope to do a spot on spring training in Arizona next year and also fishing in La Paz, Mexico. I, in no way, ascribe myself to be the reporter or interviewer that was Huell Howser. Hopefully I will get better as time goes on. But, in his memory, I’m going to call this new feature All That Glitters. The inaugural location for this new feature will be the small Dutch village of Solvang.

Located in Santa Barbara County, Solvang is the largest Danish village in America and is nestled in the Santa Ynez Valley. Los Olivos lies to the north, Lompoc to the west, and Goleta and Santa Barbara to the southeast. The literal translation of the town’s name is “sunny field.” For hundreds of years the Chumash Indians had inhabited the area but, with the arrival of the Spanish, came the mission movement. The Santa Ynez mission was built on the edge of what is present day Solvang in around 1804. It was a lonely outpost whose main goal, as with all the Spanish missions, was to convert the local native American Indians into devoted Christians.

Whether or not it was successful, is the subject of a different blog. Or better yet, a history book. Suffice to say, 100 years later the mission was abandoned and in disrepair. Just six years after the mission was built, in 1810, Mexico had declared its’ independence from Spain. At that time, the northern border of Mexico stretched all the way to what is now the border between the United States and Canada, including all of California. In the 1820s, the Mexican government proceeded to break up these lands and award huge grants, or ranchos, to soldiers, citizens, and many other of its’ favorite sons. Many of these ranchos, especially in the Santa Barbara area, were re-purposed to raise cattle and were very lucrative for a number of years. Then drought, coupled with some hard economic times, forced many of the landowners to break their ranchos up into smaller tracts. Eventually a parcel totaling 8,882 acres and centered around the old Santa Ynez mission, came under the direct control of the Santa Barbara Land and Water Company. Enter the Danish immigrants looking for a cheesy deal. (Sorry, I just had to do it.)

The 50-year period just after the American Civil War and prior to WWI, from 1865 to approximately 1914, saw a huge influx of immigration into the United States. Most of these people were from the lower and middle classes and fleeing northern and western Europe. A host of factors precipitated this mass immigration including a changing political climate, higher taxes, food shortages, and a higher population density which resulted in a lack of jobs. America was the land of opportunity, and these people came here to start a new life. In total, during that 49-year period, over 25 million new people arrived upon the shores of the United States. Approximately 300,000 of those people came from Denmark. Not a terribly high percentage when factored against that total. In fact, just slightly over one percent. But then, Denmark is a small country and 300,000 immigrants from such a small country is significant.

Being mostly farmers, these original Danes were attracted to the fertile plains of the Midwest. They settled in states such as Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin, South Dakota, Nebraska, Montana, and Texas. Some of the earliest settlers immigrated to Iowa, where they formed a thriving Danish settlement. They adored their new home and wished to extend the reach of their cultural influence to the rest of America. With that in mind, the Iowa colony sent emissaries to the far reaches of America. Texas, New Jersey, Wisconsin, and Minnesota were all considered strong locations for new colonies. And indeed, several new Danish colonies were established in these far-flung locations. But they were eventually absorbed into the surrounding communities. The Danes, as is the case with all immigrants, were becoming Americanized. But Solvang was unique for that time period.

Three emissaries were sent West in 1906 to determine the viability of a west coast colony. Their instructions were simple: explore the west coast states from Washington to California to find a location that had enough viable farmland to support two hundred families.

These men were Pastor Benedict Nordentoft, Pastor Jens Moller Gregersen, and Professor Peder Pedersen Hornsyld. Over a four-year period, they scouted several promising locations although, for one reason or another, none seemed to pan out. But they were convinced they were on the verge of finding the perfect location and in 1910 they incorporated the Danish American Colony, or DAC, to formalize their land search. Late that year Hornsyld came across an advertisement of land for sale in the Santa Ynez valley near the city of Santa Barbara. Upon investigation, they determined that the size was right, and it was within their price range.

This is where the unique location of Solvang comes into play. At that time the land that was being sold was literally in the middle of nowhere, and very difficult to reach. Mountains blocked access to the Santa Ynez Valley from the south, east, and north. Approaching from the south, the Southern Pacific Railroad had a depot in Gaviota. Approaching from the north, the Pacific Coast Railway offered a narrow-gauge spur from San Luis Obispo with a terminus in Los Olivos. The distance between the two terminals was only about 20 miles. Not far if you are driving a car over a paved highway at 60 mph. but in 1910, to get from Los Olivos to Gaviota, or the other way around, travelers had to endure several hours traveling overland in, what was appropriately called, a mud wagon, along treacherous grades on narrow dirt roads with numerous blind corners. What we now call Solvang, was simply an abandoned mission located in a field along the way. This was the feature, its’ remoteness, that made Solvang unique and prevented it from being absorbed into the surrounding communities like other Danish colonies had been.

In January of 1911, the three men struck an agreement to purchase the land from the Santa Barbara Land and Water Company. They made a down payment of $5000 and agreed to make three additional annual payments of $100,000 each to pay off the balance. I always say real estate is a solid investment. A total of 8,882 acres for a little over $300,000. My house in Bakersfield sits on 1/3 of an acre and it is worth more than that. I guess the other old saying about real estate is true also. Location! Location! Location!

Once the deal was finalized, word got out quickly. The founders advertised in all of the major Danish-American newspapers and sent out brochures to contacts in all of the Danish communities in the country. The town grew quickly as Danish settlers flocked to the new colony. Within four months a hotel had been built to house the new settlers while their homes and barns were being constructed. In November of 1911 the three founders opened a Danish-American folk school. At the time it was perhaps their crowning achievement, and it was the last such school opened in this country.

The Danish approach to education was unique and radically different from the American school system. Rather than an emphasis on names, dates, places, and equations with exams and grades, the folk school emphasized lectures and group discussions on broad moral and social issues. They stressed enlightenment through independent thought and the preservation of Danish heritage through literature,

language, and folk arts which included singing, dancing, theater, and gymnastics. The school also offered American studies that included US Geography, history, and government. School began at 9:00 AM and stretched until 6:00 PM most days. While attendance was expected it was not mandatory. The result was a well-rounded and cooperative community grounded in learning opportunities for all residents with an open dialog from multiple viewpoints.

The school was named Ungdomsskolen I Solvang, or Youth School in Solvang and was the only one like it on the west coast. Folk schools like this had long been popular in the Midwest where the first Danish settlers put down roots. Jointly owned by the three founders, it was very successful over its first two years of existence, an added enticement to lure Danish settlers from the Midwest. Benedict Nordentoft was overly ambitious and considered himself something of a visionary. In 1913 he wanted to use the momentum to expand the school and lend to its prestige. Gregersen and Hornsyld felt the timing was wrong and they should go a bit more slowly. Nordentoft took this as a personal slight and the disagreement opened a rift between the three that was never repaired. For his part, Nordentoft pushed forward, collecting thousands of dollars in donations, which he used to build Atterdag College. With the money he raised, and a lot of volunteer labor, Nordentoft had the college built in six months and it was open in time for the 1914-1915 semester.

While this was going on the colony was suffering growing pains. Mads Frese had been added as a fourth DAC director and its chief sales agent. The mild climate, close-knit Danish community, and folk school were all solid reasons for new settlers to want to come to Solvang, as were the close personal friendships the four directors had with many of the new arrivals. For these reasons land sales were brisk in 1911 and the DAC was able to make the initial $100,000 payment in 1912 easily. But conditions were less than idyllic. Summers could be brutally hot and the winters drier than anticipated. Services, such as water and electricity, were still some years off with ground water too deep to tap for wells. The roads, mostly dirt, were in poor condition. The colony was isolated and difficult to reach and, while that was all well and good to allow the Danes to retain their sense of cultural identity, it also had the reverse effect and isolated them from the outside world. The winter of 1911-1912 was unusually wet, damaging crops which resulted in a poor harvest. After the first wave of settiers, the DAC was finding it almost impossible to sell additional parcels and was only able to make the second payment by way of a two-month extension. This was one of the main reasons that Gregersen and Hornsyld had tried to dissuade Nordentoft from expanding the folk school so rapidly. It became difficult to intice additional colonists and some that were already there talked of leaving. The winter of 1912-1913 was marked by a drought, leading to another poor harvest. By September, with only $15,000 raised, things looked bleak, and so it was decided to honor the terms of their agreement and return all the unsold land parcels to the Santa Barbara Land and Water Company. This represented almost 6,000 acres of land, which was immediately put back up for sale.

They did not completely give up though. Not wanting to share the land with non-Danish immigrants, the DAC approached one of its own, Jens Moller Gregersen. Many felt that, with his keen business acumen, Gregersen was the one to take over Solvang’s financial affairs. He was well liked and well respected, and it was felt that if he approached investors as a private individual, rather than a board member of the DAC, they may be more responsive to investing in Solvang. Gregersen went on a two-month crusade, even resigning his position as pastor to devote all of his time to the project. In that short window of time, he was able to convince 25 investors to buy back the remaining land from the Santa Barbara Land and Water Company. With most of the original land now in Danish hands, per the original plan, the future of Solvang seemed secure. With that, the DAC, its’ primary mission complete, was summarily dissolved.

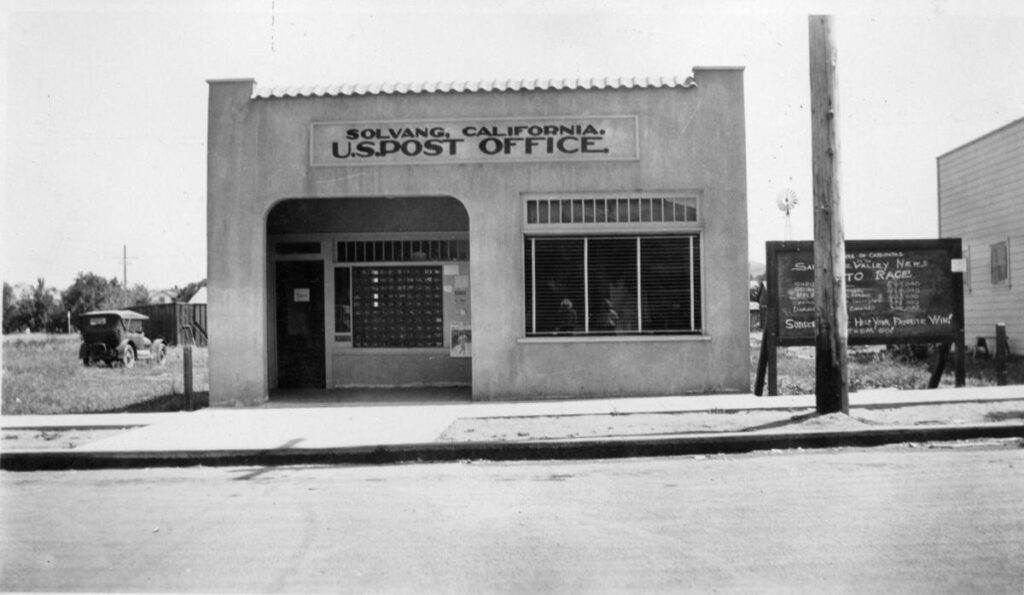

J.M. Gregersen returned to Solvang and, fittingly, became the president of the newly formed Santa Ynez Valley Bank. Located in downtown Solvang, it was the first bank ever built in the Santa Ynez Valley. He worked there until his death in 1917. Upon his passing, Gregersen’s old friend and fellow founder, Peder Hornsyld, took over his duties at the bank. He simultaneously filled the role of Solvang postmaster. Hornsyld passed away in 1928. Meanwhile, Benedict Nordentoft found himself the sole owner of Atterdag college. Rather than rest on his laurels, he spent many years promoting the college and physically building paths, bridges, and outdoor speaking platforms. He married in 1918 and by 1921 he and his wife had two young children. They found themselves with a decision to make. Do they stay in Solvang and raise two American children, or do they return to Denmark to raise the children as true Danes? In the end, the answer was Denmark. Nordentoft sold Atterdag College and the family returned to Denmark, settling in Kolding where he became active as a pastor at St. Nicolai church, an educator, and a sought-after speaker. In total, he and his wife had 11 children, all 11 with the middle name Atterdag. He passed away in 1942.

When formed in 1911, Solvang was set up as an agricultural community. The majority of Danish immigrants were farmers or dairymen, and they brought these skills to their new home. The farms were labor intensive and therefore very small. They also practiced what is known as dry farming, meaning they planted crops in the wetter winter months but didn’t grow anything during the hot dry summer months. Since they only harvested one crop a year, the farmers had to find other ways to raise money. This means they kept chickens for eggs or hogs for slaughter. Some even kept a small herd of dairy cows. At that time the Dutch were considered the world leaders in dairy products. What do you want to bet that a lot of those Wisconsin cheese makers have Danish roots? Raising dairy cattle was second nature to them and most of the dairy products coming out of the Santa Ynez Valley at the time, were centered around Solvang. Eventually they formed a dairy co-op that had roughly two dozen members, give or take.

Life in Solvang was far from easy in those first 20 years or so. Farmers’ wives had to prepare meals for the farmers and hired hands in the fields. This included breakfast, midmorning coffee, lunch, midafternoon coffee, dinner, and dessert. They maintained small gardens for themselves and preserved fruits, vegetables, and meats. They hand washed, starched, and ironed clothes for the entire family. Not only did they also have the daily requirement of dusting, washing the floors, cleaning the dishes, and sewing tattered clothing but they had to tend chickens, milk the family cow, and make butter and cheese. All this was done by hand, with nary a Rosie the robot in sight. Meanwhile, the men of the family toiled in the fields from sunrise to sunset using horse drawn plows and the sweat of their brows to cultivate a meager living from the dry soil.

They weren’t all farmers though. Like any town, Solvang had to provide the basic amenities for its’ residents. Small businesses such as blacksmithing, feed and grain stores, the aforementioned bank, general stores, furniture stores, coffee shops and restaurants, and stores selling work boots and clothing sprang up overnight. As the automobile entered the picture, gas stations and garages appeared. The Solvang Garage opened its’ doors in 1913. As early as 1912 one enterprising gentleman, by the name of Peder Madsen, opened an establishment that was part barber shop offering haircuts AND shaves, part pool hall, provided baths, and sold cigars and beer. His became a thriving business.

With all of this construction the town grew quickly. The buildings though, were not of the typical Danish construction with which we are now so familiar. Instead, the buildings were of western and Spanish style architecture. You see, even though the Dutch wanted to retain their heritage and sense of identity, they also wanted to blend in as new American citizens. For decades, in spite of its Dutch heritage, Solvang, for the most part, looked like any other small town in America. And, like any small town, Solvang required basic services. Remember, this was the early part of the 20th century and the standard of living in America was changing rapidly at that time. People where just gaining access to basic amenities that we now take for granted. Suddenly, they had use of electricity in their homes. First for lighting but soon all manner of electrical appliances followed. There was natural gas for cooking, hot and cold running water, flush toilets. But in tiny and isolated Solvang it took a while before even the most basic of services became available. The first streetlight, a Coleman Lantern strung on a wire, appeared in 1921. Actual electricity didn’t arrive until 1923. That was only in the town proper. The outlying homesteads didn’t get electricity until 1929. Actual streetlights on a grid appeared in 1925 as two square blocks of downtown were illuminated. The town didn’t have a regular doctor until 1925.

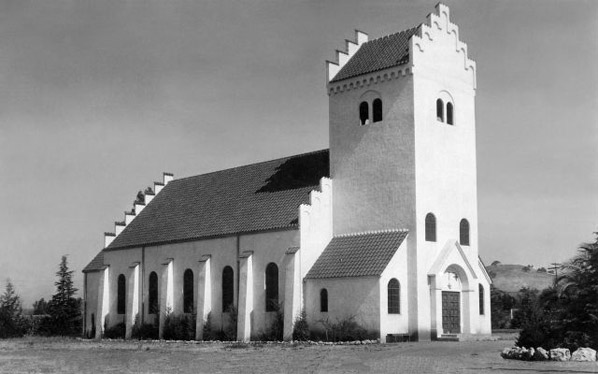

A very religious people, the Dutch had wanted a church from the outset. But they had to be satisfied with services held in any available building or possibly outdoors. The first church was built in 1928. The town acquired its first stop sign in 1929 but it wasn’t until 1945 that they actually had sidewalks, curbs, and address numbers. While Solvang had a post office, regular postal delivery service didn’t start until 1947. It wasn’t until 1954 that the town actually had an integrated sewer and water service. And in 1968 Solvang got its’ very first stoplight.

Still, the town thrived. Mostly through cooperation. If the bakery down the street ran out of flour the other bakery in town would send over enough flour to get them through the crisis. If a farmer became ill or injured, the other farmers would lend a hand so he would not lose his crops. Probably, a lot of this had to do with the teachings at Atterdag. The school instilled a sense of pride and community into the residents of Solvang. They were taught that they were all in this together and if the colony was going to survive, it would be through pride, fellowship, and a common goal.

Solvang began to change. Slowly at first. The roads had become better constructed and easier to travel and, with the advent of the automobile, more people were coming to Solvang. A number of them came to stay. Many of these were immigrants from northern Europe and, by the 1920s, made up roughly 15% of the population. That number would swell to fully one third of the population in the 1930s. Also, After WWI, the United States clamped down somewhat on its immigration policies. This meant fewer immigrants from Denmark were entering the country and, therefore, no new infusions of Danish culture. Danish had always been the primary language spoken in Solvang but, to remain competitive, shop owners now began to advertise in English as well. The church began to offer services in English and English was being spoken at Atterdag college more frequently. At least that was the case until the school closed. The idea of the Danish folk school had initially been very popular when they were started in the Midwest. There is something to be said for their philosophy about teaching and encouraging community spirit. But, as the Danish people in Solvang and other parts of the country became more Americanized, the folk schools became something of an anachronism and, one by one, they began to close. Simply put, with the coming of the industrial revolution, America was fast becoming a more capitalist nation. This was in stark contrast to the Dutch philosophy, which was, at its heart, more of a socialist movement. The young people of Solvang had come to consider themselves Americans and they wanted the same advantages all Americans had. Perhaps Nordentoft had seen this in the cards, and it was why he decided to move his family back to Denmark. In any event, the reverend Marius Krog had led the college for five years. With dwindling attendance, he knew the day of the folk school had passed so in 1937 he resigned. With no one to take his place, the college simply closed down after nearly a quarter of a century.

The folk school had been a cornerstone of the founder’s plan for Solvang. It’s closure, perhaps, signaled more changes on the horizon. As I said, things had slowly been changing all through the 20s and the 30s. But it was after WWII that things really began to change, and quickly as the town moved away from its’ agricultural roots. The town fathers recognized the uniqueness that was Solvang and wanted to capitalize on that through tourism. Not only did the business model change, but the actual appearance of the town changed. Join me next week to find out how all of this came about. And, if you have never been to Solvang, I will enlighten you with what to do and where and when to go to Solvang.

This has been a fun topic to write about. I myself first went to Solvang in 1978 and have returned once or twice a year almost every year since. In talking to some of the long-time residents and reading up, I learned a lot about Solvang that I had never known before. This first part has been an AMAZING (you are welcome, Huell) bit of a history lesson, explaining how and why Solvang was founded. I want to personally thank Linda Palmer and Kirsten Klitgaard who work with the Elverhoj Museum in Solvang on 2nd St. for taking the time to educate me. I also want to say thanks to Ann Dittmer and Esther Jacobsen Bates who wrote the book “The Spirit of Solvang”. Until then remember, always swing for the fences.